The story so far:

My grandmother and mother were born in Bell Ville, originally named Fraile Muerto, and this series of posts is the result of my research into this village, later a town. There were English farmers in the countryside and (mainly) Italian immigrants in the town, and I descend from both.

Part 1: The history of the area up to the mid nineteenth century.

Part 2: The arrival of the English farming pioneers as typified by Richard Seymour and Frank Goodricke, who resided at their farm Monte Molino from 1865-68; their first encounter with marauding indians; headman Lisada’s gesture of friendship to an indian scouting party.

For the moment Dick Seymour and Frank Goodricke realised that cattle-farming was the profitable way forward; the conditions were ideal. The two English partners set about obtaining bullocks, but learned the hard way that it was only going to work if they were purchased a long way from Monte Molino. There were plenty available locally, of course, but they soon found that no matter how carefully the animals were locked in at night, they had often managed to escape by the following morning and returned to their previous abode. After one such occasion when they had to recover them across great distances on three consecutive mornings, they raised the height of the gates to 6 feet. On the fourth morning after another wearying foray into the countryside, they realised that the only solution was to get one of their peons to sleep with them. The creatures eventually settled down, but all the exercise had caused them to lose a lot of weight.

And of course there was the matter of the indian raids. There was a pattern to them. If they could get away with it they stole everything they could get their hands on at the farm – weapons, food, clothes – and were prepared to kill to do it. However the main purpose was to steal livestock to take back to their people.

Horses were greatly sought after, and cattle. Sheep rustling however had not yet taken hold because the creatures didn’t move fast enough and shared the country’s custom of sleeping in the middle of the day, lying down on the ground and huddling stubbornly together for several hours in the early afternoon. Seymour and Goodricke thus judged that investing in sheep would be a good idea. Because of indian raids they had been unable to get the necessary shearing tools in time, so it was late in the season by the time they took their wool for sale, and made little out of it.

But there were other problems. They were easy prey to the local grey foxes and the puma. The puma is now only to be found in hilly areas or in the desolate parts of Patagonia, in those days it existed in plentiful numbers on the plains. Seymour records in his book that they were forced to kill six in one year because a single puma could despatch 20 sheep in one night. He reports that the largest they ever caught measured nine feet from nose to tail.

But there were other problems. They were easy prey to the local grey foxes and the puma. The puma is now only to be found in hilly areas or in the desolate parts of Patagonia, in those days it existed in plentiful numbers on the plains. Seymour records in his book that they were forced to kill six in one year because a single puma could despatch 20 sheep in one night. He reports that the largest they ever caught measured nine feet from nose to tail.

The worse Indian raid they were to encounter was in late September 1866 when Seymour and Goodricke rode the 15 miles to a neighbouring farm by the name of Monte Llovedor (Rainy Grove) to see how their friends John Pearson and Thomas Edwardes were faring in setting up their farm. At that point they had constructed a small fort surrounded by a ditch, and were shortly going to build a house. Pearson was away on business, but Edwardes and his capataz Dan Mulligan, two English and two local peons greeted them cheerfully as they worked on the ditch. After a pleasant few hours Seymour’s party left mid afternoon, taking Mulligan with them because Edwardes had agreed to buy one of the Monte Molino horses, and the headman was to bring it back to Monte Llovedor the following day.

The following morning one of the farmhands reported that the Indians were in the vicinity once again. Mulligan decided to stay on for a couple more days at Monte Molino because he did not fancy his chances returning to Monte Llovedor with his horse and the other in tow. The day after his departure all seemed quiet so Goodricke and Lisada set out to check whether there were any Indians in the neighbourhood, and to pick up any stray cattle they might have left behind.

Nine miles later they came upon traces of a large Indian encampment close to the river where they found strewn around a number of worthless items, evidently the property of English settlers because one of them was a book in English with Pearson’s name on the fly cover. Now seriously concerned, they quickly headed back to Monte Molino to get reinforcements, fast horses and weapons. With Seymour they headed for Monte Llovedor as quickly as possible.

When they got there they saw with horror that the fort had been destroyed, and the only sound emanating from the site was a mournful howling of dogs. Fire had consumed the area, there were charred remains of two carts with trunks broken open and all the contents which the Indians had not taken away such as letters and books, were scattered about in all directions. In the ditch were the remains of three people – Edwardes and the two English farmhands.

Later they heard the story from one of the farmhands who had been there. The men were busy preparing their evening meal in their tent when they heard the sound of horsemen approaching at great speed. They seized their arms and ran to the recently finished fort. There were about 200 riders surrounding them, the leader of which gave them to understand through the gaucho interpreter that if they gave up everything their lives would be spared. Edwardes told them they could take what they wanted from the tent, but that if they entered the fort they would be fired at.

Unfortunately as they had only just been digging the ditch they had not yet disposed of the spoil, which was piled high on either side, and this the indians used to conceal themselves. With their lances they punched holes in the mounds, stuffed them with dried grass and set fire to them. Surrounded by fire and smoke, the besieged men eventually had to run for it, and were murdered one by one as they tried to get beyond the fire. The peón telling the story was the only one spared because he had a wounded leg and had managed to hide in the ditch. When discovered the gaucho interceded on his behalf with the Indians, because he knew him. He eventually managed to limp his way to a neighbouring estancia and from there was taken to Fraile Muerto to get medical attention.

Monte Llovedor was abandoned, and Pearson himself struggled on for three years, eventually perishing of sunstroke in 1869. It was a long time before new settlers came back to the area.

With these sorts of tragic stories it was small wonder that the Indian raid on an English farm at Monte de la Leña (Firewood Grove) merely caused amusement when it was later related in the village. The indians had surprised the Europeans within while the latter were carrying out their ablutions and getting dressed early one cold morning and they had no option but to scramble onto the roof of their recently finished hut in various stages of undress, huddling together for warmth and watching helplessly while the marauders stole everything they could lay their hands on.

It was now fifteen months since Dick Seymour had arrived at Monte Molino, and the railway had at last reached Fraile Muerto, thankfully making the stuffy, horse-drawn coaches a thing of the past. The village now boasted a population of 1000 and many new houses had been built. The Chief of Police had increased powers to keep law and order and had twelve enlisted men to command, in addition to volunteers when indian raids threatened.

It was a relief when that a bridge across the river had been built which gave access to the railway station, for up until that point getting goods home was a major exercise, taking up to three days to complete. The raft was not large enough to carry carts, so everything had to be loaded and unloaded between the station and the raft, and after being ferried across, had again to be placed in carts to deliver to the fonda in the village, there to await their own transport.

Seymour was an acute observer of the people around him, and noticed that the gauchos and locals had the refinement and self-controlled manners of their Spanish ancestors, yet not their morals and religious fervour – and judged that missionaries could well do some good work there.

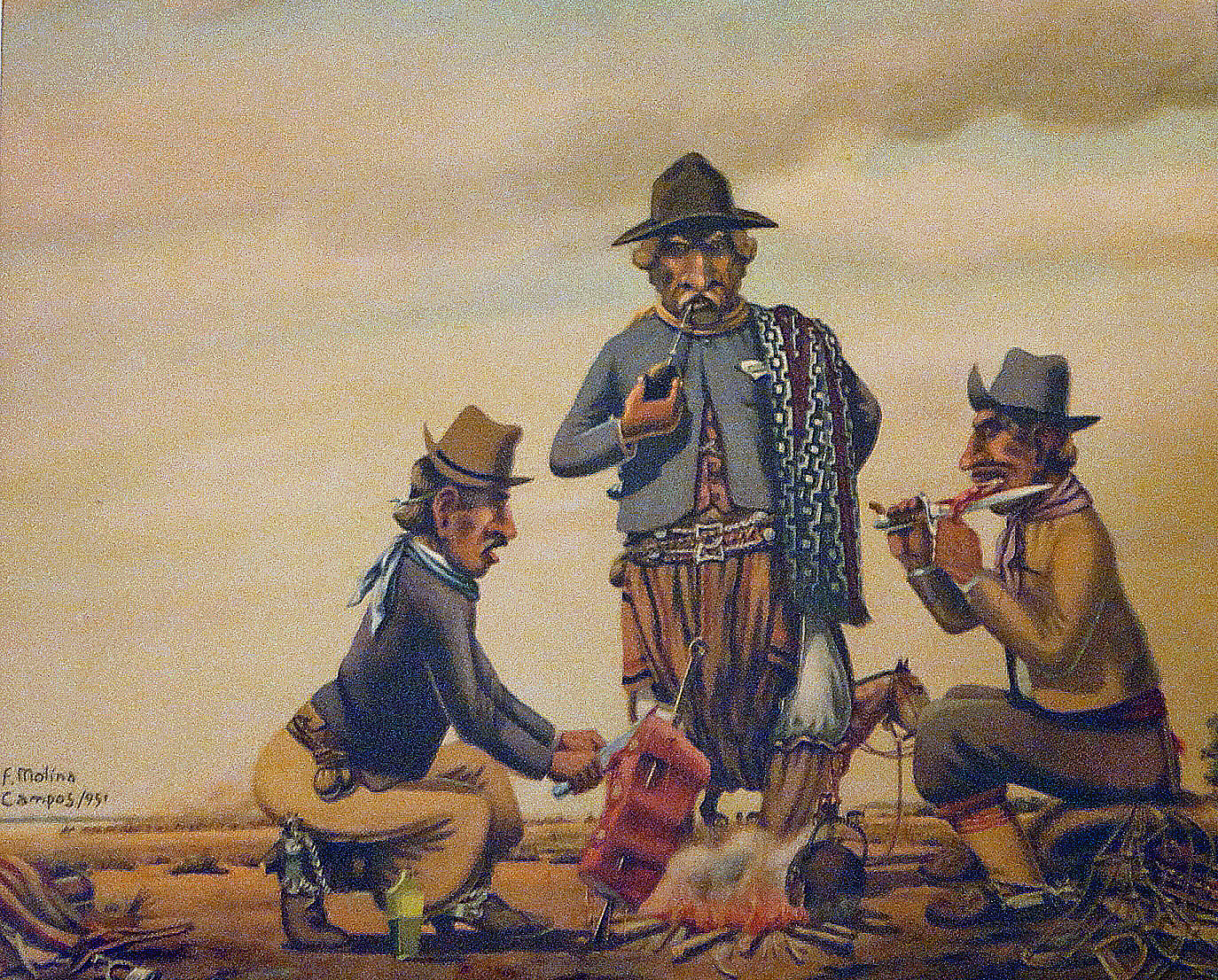

Traditional gaucho with his constant companion...

He had mixed feelings about the gaucho – so admired these days as the essence of the Argentine spirit. His experience of them in the mid nineteenth century was that they were rugged loaners of unsociable and reclusive disposition; wedded to their horses, they never stayed anywhere for very long. Indian tribes often had a gaucho in tow to act as interpreter with the farmers, and these individuals led particularly tough lives.

...in good times and bad (Molina Campos)

There were various interesting characters in the village which Seymour ably described.

The rough and ready bar where a man could get a meal – the fonda - was run by an Italian known as Don Pepe with his partner Luigi...

The rough and ready bar where a man could get a meal – the fonda - was run by an Italian known as Don Pepe with his partner Luigi...

Don Pepe had previously been a priest, choosing to renounce monastic life for a bit more excitement. As he told Seymour, he was then able to give free rein to the swearing which had previously been denied him… that is until he had caught cholera a few years back. He was so surprised and grateful to have survived that he vowed never to swear again.

One of the bilingual residents of the village considered himself to be a ‘gentleman’ of the highest order descended from one of the River Plate’s finest families. He was considered local royalty, particularly in view of his fondness for the English language and Shakespeare, whose lengthy quotes held the locals in thrall.

Don Nazario Casas, the Chief of Police who had a militia of 12 soldiers and some volunteers, the totality of their defence against the Indians in the area, took his job very seriously, and on one occasion had one of the farmhands at Monte Molino put to death. This man had deserted from the army, having murdered one of his officers and gone on the run, arriving at the farm looking for work, which was given him in ignorance of his past. And there it would have remained, had the man not given in to the temptation of going to the village on payday. Even then nothing would have happened if he had behaved himself, but a pattern was established each month, whereby he started drinking and gambling, the former affecting his behaviour with the latter, and he became known by all. His luck ran out when an officer passing through Fraile Muerto recognised him, knew what he had done, and reported him. He was arrested, tried and shot.

Seymour was greatly impressed by the Catholic priest, who was Italian. He says -

“…He was not a very clerical character, but pleasant and good-natured, and having been educated as a doctor did all he could for the bodies of his parishioners, and I trust also for their souls. What curious vicissitudes of life had at length landed him in this secluded part of the Argentine Republic I do not know, but he was a well-informed man, acquainted with several modern languages and a very pleasant companion. He came into the fonda at one time for his meals, while his house was building, and it was there I used to see him. During the cholera time he exerted himself nobly for the people, and I hope may have made some lasting impression on them. “

The village’s doctor was Don Bartolo, a clever little man, well-informed about general things and devoted to gardening. He always welcomed the foreigners hospitably to his little house, where his pretty niece Doña Flores would serve them refreshments. He had two club feet, so could only hobble around town. When as a result he was unable to go to the rescue of a farmhand who had fallen on a fence while carrying a sheep on his pommel and broken his leg, Dick Seymour helped out and set the man’s thigh; he recovered well and earned praise from Don Bartolo.

Dick was impressed with the general health of the population, remarking that they rarely got ill, and when they did they healed quickly. He calculated however that three people in five had at some point had smallpox in the past, but the epidemic had clearly been overcome. Not so with cholera, which he witnessed during his years in Argentina. He makes one other comment –

“…The only peculiarity which I am quite unable to account for is that in spite of the large amount of fresh pure air, they find any cuts or wounds very difficult to cure, and lockjaw will come on from the most trifling accident.“

Unbeknown to him this was tetanus, for which a vaccine was not developed till 1924.

Gauchos barbequeueing their evening meal. Note the one on the right is holding the meat between his teeth and his left hand, while his right hand holds the knife or facón and slices it away from his hand. This is the traditional way of eating beef when plates are not available, or simply because they are outdoors.

(Painting by Molina Campos)

3 comments:

Another interesting slice of Argentinian history.

Just wanted to say I am so glad you are back writing. Love the pictures interspersed with the story.

I'm far behind in the readings but I've been out of town. When I recover I will be back to read the newer installments. Hope you're doing well my friend. Hugs. xx

Post a Comment