Link to The Dressmaker Part 1 of 5 - "Early Struggles": Click HERE

Link to The Dressmaker Part 3 of 5 - "Doña Sol's Daughter": Click HERE

Link to The Dressmaker Part 3 of 5 - "Doña Sol's Daughter": Click HERE

Pastures New

Sol grew into a very attractive young woman with light eyes which sparkled when she laughed, and long brown hair which she wore in a bun at the nape of her neck. She had many admirers, one of whom was a Spanish lad named José; her parents particularly favoured him, perhaps because of his nationality, although they knew he had a temper. He was very much in love with her, but she didn’t return his affection in quite the same way. She found his passionate and intense nature tiresome and his poor prospects disappointing, and while it pleased her to have a partner to take her to the cinema occasionally, she did her best to hold him at arms length.

.

This state of affairs continued until her mid-twenties, when early one fresh spring morning when the jacarandas were in flower either side of the main avenues which led into the centre of the city, she made her way by tram to a haberdashery to purchase sewing materials for her employer.

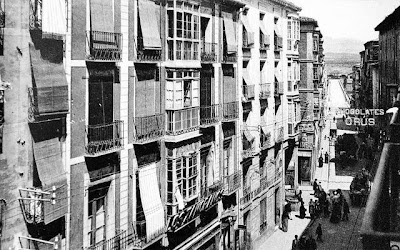

Contemporary Tram

Another customer was already there before her. Prosperous and well-connected, Don Pedro Quintana was in his mid fifties, and as he purchased a bolt of cloth for his wife he noticed the young and shapely Soledad at the next counter.

He admired her petite profile for a while, taking in her light brown hair and dazzling smile, and as she turned towards him to look at something on a shelf above his head he saw her fine cheekbones, hazel eyes and creamy skin. From that moment onwards he was smitten, and hurriedly paid for his goods to wait for her outside. As she emerged from the shop he approached her, politely doffing his hat with a smile, and engaged her in conversation.

What Soledad saw was a smartly dressed middle-aged gentleman inclined to corpulence who sported a silver cane and a smart fedora, wore a gold ring on one of his carefully manicured hands - and had good teeth. Accustomed to sizing up people at a glance, what she saw was prosperity, good living and (probably) healthy habits – everything she yearned for.

For someone in her reduced circumstances, what came next was predictable and not unwelcome – it was clear he wanted her as his mistress, and the prospect of going from penury to some degree of security, even if not long term, was irresistible. With charm and modesty she told him that he would have to talk to her elder brothers, and some days later a meeting took place. Her brothers satisfied themselves that he could afford to keep her and that she would have her own home, before agreeing to his terms.

A week later she had packed up her few belongings and said her goodbyes to her parents and her dismayed employer, setting off with her brothers to the apartment in the smart part of town where Don Pedro had rented a property in preparation for her arrival. Well and truly in love, he was waiting for her in a sitting room full of red roses.

A week later she had packed up her few belongings and said her goodbyes to her parents and her dismayed employer, setting off with her brothers to the apartment in the smart part of town where Don Pedro had rented a property in preparation for her arrival. Well and truly in love, he was waiting for her in a sitting room full of red roses.

Her employer was not the only dismayed party – Don Pedro’s wife Victoria, a well-known society lady, had to endure the humiliation of being told by her husband that he was leaving her to go and live with someone half his age.

He had assured her she would want for nothing (except his presence of course, and she had never had much of that in recent years) but the issue was really about going out and about in genteel Buenos Aires society with people whispering pityingly about her behind her back, not to mention her family who ‘had always known he was bad through and through’ and whose disapproval she had ignored when she married him. They had four children – two daughters and two sons ranging in age from 33 to 21, and he may well have also been a grandfather by then.

He had assured her she would want for nothing (except his presence of course, and she had never had much of that in recent years) but the issue was really about going out and about in genteel Buenos Aires society with people whispering pityingly about her behind her back, not to mention her family who ‘had always known he was bad through and through’ and whose disapproval she had ignored when she married him. They had four children – two daughters and two sons ranging in age from 33 to 21, and he may well have also been a grandfather by then.

Meanwhile, Sol’s Spanish suitor José was inconsolable and it was unfortunate that in the circles he moved, guns were the means of settling old scores. He had no plans to harm the woman he loved however; instead he turned a gun on himself, putting a bullet through his temple. He died instantly. Sol was by then far removed from the barrio where they had lived, and she only heard second-hand from her youngest brother that his family held her responsible.

Don Pedro Quintana was a member of the Quintana de Aldama family, well-to-do members of Argentine society, some of whose ancestors during the 19th century had colonised the eastern section of the province of Córdoba, north of Buenos Aires; there is in fact a town named after them. Thus by leaving his family and setting up home with a mistress he became the black sheep of the family, and henceforth anything he did – or didn’t - was merely living up to their low expectations.

The regular income he received from his family ceased, and they ignored Sol’s very existence. It was a brave move for a family man in his fifties, and only one close friend from his old life kept in touch with them, Coronel Jorge Espuela, a much respected military and political figure of the time after whom he had named one of his children. None of his other friends and relations ever visited them at the apartment.

Downtown Buenos Aires in the 1920s

Sol never looked back. She settled happily into the unaccustomed comfort of a spacious apartment with a live-in maid. Don Pedro had never worked and they needed an income; idleness was not in her nature so before long she had started up her own dressmaking business at the flat. He was a man-about-town with many contacts, and a word in the right ear got her plenty of commissions among the society ladies with whom he mingled. At a time when Paris fashions were slavishly followed, the word soon spread that the modest little mouse living with him was a gifted seamstress, and while they may have been scathing about her social status behind her back, they recognised her unique abilities and were happy to offer her their patronage.

(The names and some of the places have been changed.)

Part 3: Doña Sol’s daughter

-oOo-

Photo Finish:

from Lonicera's non-digital archives

Oleander

Bluebells (Spanish variety)

Guanacos, Patagonia, Argentina

The only true British primrose

Back to the top: Click HERE

Go to Part 3 of 5 "Doña Sol's Daughter": Click HERE

-oOo-